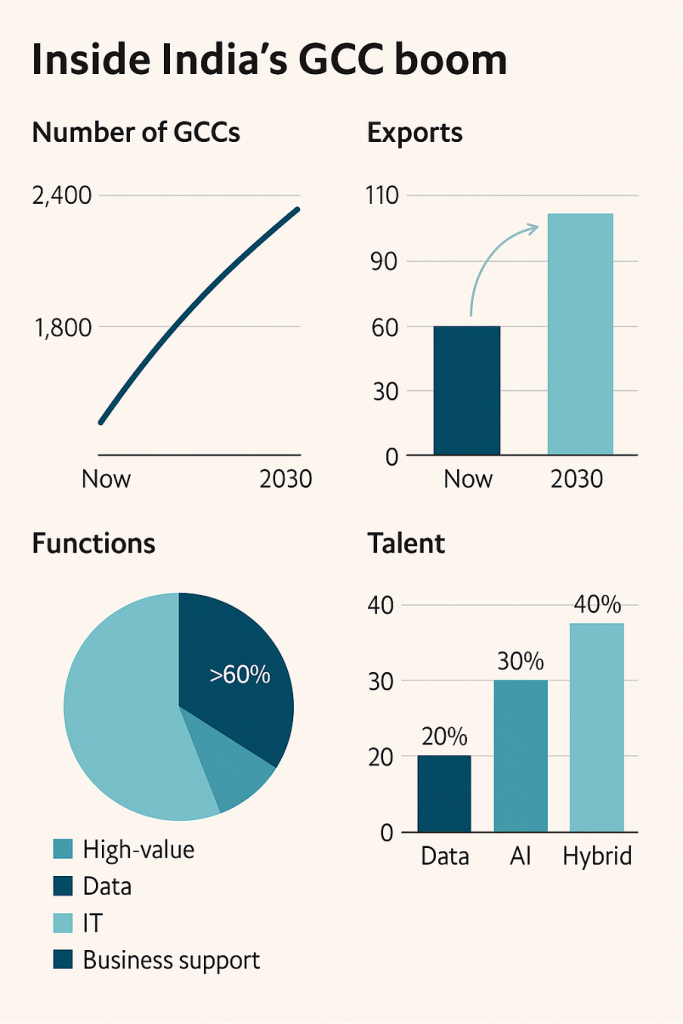

When Washington tightens its visa screws, the unintended beneficiary often lives halfway across the world. India’s ever-expanding ecosystem of Global Capability Centres (GCCs) is a case in point. A new report by TeamLease Services forecasts that the number of such centres, back-offices, engineering units, analytics labs and everything in between will rise from roughly 1,800 today to 2,400 by 2030. Their combined export value could exceed $110 billion, nearly doubling from current levels. For a country long accused of supplying only cheap labour, this may be the most significant rebranding exercise yet.

The quiet rise of corporate India

GCCs are not new. Multinationals began setting up Indian outposts two decades ago to exploit abundant, low-cost technical talent. What is changing is the nature of the work. Once limited to payroll processing and call-centre tasks, these centres now handle product design, cloud-architecture, cybersecurity, and even R&D in semiconductor and electric-vehicle technologies. A generation of Indian engineers, trained first to execute and now to innovate, are repositioning the country’s back-office reputation into that of a global innovation factory.

India’s strengths are well rehearsed: scale of talent, cost efficiency, and an improving regulatory climate. States from Telangana to Uttar Pradesh have begun courting GCCs with tailored policies and incentives. The result is a proliferation not only in traditional hubs like Bengaluru and Hyderabad, but in smaller cities—Coimbatore, Kochi, Nagpur—that now boast fledgling “nano-GCCs” of fewer than a hundred employees.

Visa headwinds, tailwinds for India

A curious twist is that America’s tightening of the H-1B visa regime, once thought to threaten Indian IT, has in fact reinforced this domestic boom. According to TeamLease, the impact of such visa curbs has been “minimal”. Firms, it seems, would rather expand in India than navigate unpredictable immigration policy. “People don’t change hiring at the whim of politics,” notes one industry executive—an understatement that conceals a profound structural shift.

If talent cannot travel to the work, the work travels to the talent. This dynamic—accelerated by pandemic-era digitalisation and cost pressures—is remaking global operating models. India, with its scale and ecosystem depth, offers multinational companies a dependable alternative to off-shoring headaches elsewhere.

From back-office to brain trust

The average GCC still saves its parent firm 30–40 per cent on costs, but the larger story is value, not thrift. In the newest centres, one hears fewer accents of help-desk English and more conversations about AI pipelines, data governance and digital-twin simulations. The EY and Nasscom-Zinnov studies cited alongside TeamLease estimate that by 2030, over 60 per cent of new GCC jobs will be in high-value domains such as data engineering, product development and R&D.

That demands a new kind of workforce. India’s graduate glut has always been an advantage in numbers; now quality will matter more. Wage inflation for skilled engineers is already climbing, a reminder that even India’s cost edge is finite. But the flywheel of scale and experience is difficult to replicate elsewhere. Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia are trying; few have India’s depth of managerial talent or English-language fluency.

An ecosystem matures

Real-estate data underscore the trend. GCCs accounted for nearly 40 per cent of India’s Grade-A office absorption in 2025, up sharply from post-pandemic lows. Developers are racing to offer campus-style facilities with on-site data centres, wellness zones and green certifications—an unlikely aesthetic evolution of what once began as fluorescent cubicles.

At the same time, the rise of smaller, distributed GCCs is diversifying risk. Rather than mega-centres with thousands of employees, companies are experimenting with “hub-and-spoke” models, setting up multiple micro-units across cities. The approach improves resilience and broadens the talent funnel, even if it complicates governance and cybersecurity oversight.

Winners and risks

For global firms, the logic is compelling. Locating high-end digital functions in India delivers both cost efficiency and time-zone coverage, while aligning with “China + 1” diversification strategies. For India, the upside is twofold: high-quality jobs and integration into the global value chain beyond IT services.

But challenges lurk. Wage pressures, talent poaching and uneven infrastructure could test sustainability. Not all GCCs will evolve into innovation engines; many may remain transactional support units. And as data-sovereignty and compliance regimes tighten worldwide, firms must guard against regulatory snags. The notion of India as a “low-risk” offshore base is valid only if security, privacy and governance keep pace with growth.

A quiet transformation

Still, the trajectory is unmistakable. In the 1990s, India exported software developers. In the 2000s, it exported call-centre voices. In the 2020s, it appears to be exporting capability itself—embedded within multinational structures rather than contracts.

By 2030, nearly every Fortune 500 firm is expected to have some strategic capability rooted in India. The old outsourcing stereotype—cheap labour, repetitive work—will look as dated as the dial-up modem. What emerges instead is a subtler form of globalisation: one in which the work migrates, the value stays, and India’s cubicles quietly become control rooms of the world’s digital economy.